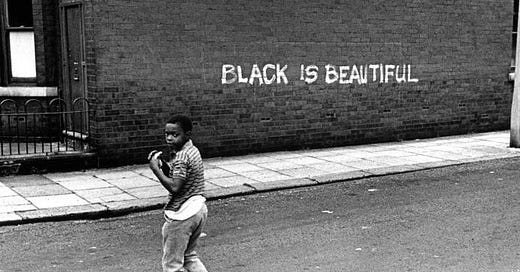

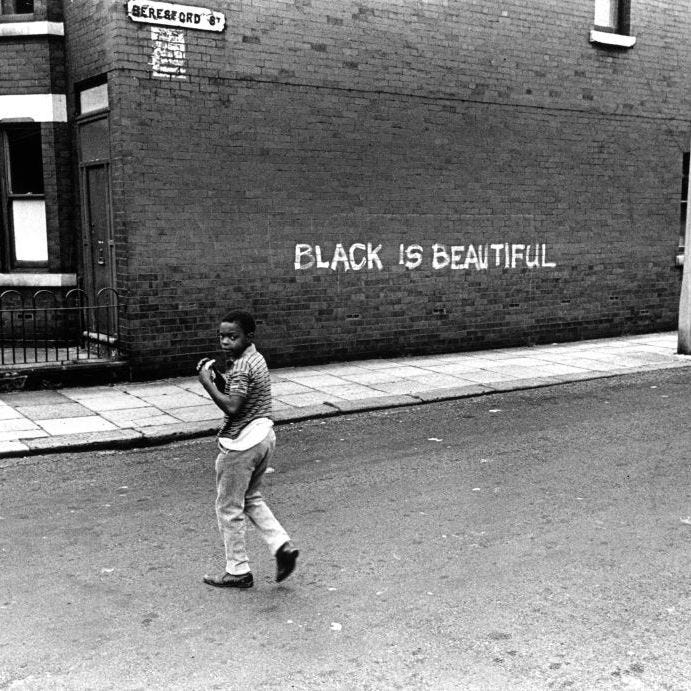

There is power in a name.

My parents took this very seriously. Each of their children were given names that took explaining. My oldest sister bears an Arabic name that means “Beautiful.” The sister that falls second in the birthing order travels the world with a French name that means “Sun.” I was (in part) named after my father and his father before hi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Son Do Move to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.