the Empathy List #109: Trey Ferguson Can't Reconvert Anybody

Pastor Trey Ferguson on how to stay humble on Twitter, loving your deconverted friends, and the "outsider" theologians you must read.

Hello friend, Liz here.

I’m coming to you today with a conversation between myself and pastor,

, a “Bapticostal” who first trained in a white conservative evangelical seminary that shall not be named… before dropping out during his last semester. He felt he had to check so much of himself “at the door,” including his desire to make space for questions, empathy and nuance.As you can imagine, his decision to leave seminary so close to graduation was inconvenient and baffling to some in his life; however, it paid off. After years learning from male European theologians, he instead reenrolled in one of the U.S.’s historically black seminaries. This offered him a much wider ranging theological education, stretching beyond the borders of normative “white male theology” and into the territory of “the other theologians,” the ones speaking from the margins, to the margins.

Trey also interests me because he’s another person who exhibits both firmness and gentleness online (on Twitter/X specifically), even when dogged by the Theobros. ;-)

But humility does not come naturally to any of us. He learned to eat humble pie during his undergraduate years at the University of Miami where he was one of the few Christians he knew on campus. Meaning, he had many, many friends of different (or no) faith.

He told me, “When you’re surrounded by people who think the same as you do, it’s easy to be loud and brash. Nobody’s really going to check you because you’re all on the same page. But when you have people [around you] who either don’t share your beliefs or find your beliefs laughable, it encourages you to reexamine yourself and to not hold your beliefs as tightly.”

In other words, he learned empathy from spending time with those unlike himself, and now, he extends that empathy to his congregants and followers alike. And that’s the sort of ministry I can get behind.

I hope you enjoy meeting Trey, and afterward, don’t forget to follow him at all the places. He’s famous on Twitter, but I especially like Trey’s Q&A at his substack The Son Do Move— you can ask him all your crazy questions about the Bible… ;-) And since I myself don’t have an mDiv, I’m gunna send you his way so you can lob your hardest Bibley questions at him instead of me, mmk? (Ahem, lob kindly/gently/respectfully.)

Cheers to hard questions and deep thoughts, my friends.

Thanks for reading.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

Trey Ferguson, pastor and author, talks about his lifetime spent at church, staying humble on Twitter, how to love your deconverted friends, and all the theologians you’ve never read but need to read ASAP.

Born on a Wednesday, in Church that Sunday

TREY: There are people who literally tell you the date they got saved. I’m not one of those people at all. I grew up in the church is what it comes down to. My mom loves telling the story of how I was born on Wednesday and in church that Sunday—literally. I was always around the church, doing all the extracurriculars: children’s choir rehearsal, Sunday school, church step team, playing for the church’s basketball team…. That was the water I was swimming in.

And right around the age of 9, I started telling people I wanted to be a preacher. I specifically remember telling Reverend Dr. Lance Watson, pastor of St. Paul’s Baptist Church in Richmond. He was like, “Alright, cool. First step: read the Bible.”

And I was like, “Hell, no, I’m not doing that.” So, I gave up on that dream for a little bit; I was going to be a fireman instead.

LIZ: Wait, what did you think about the Bible?

TREY: It was way too long and boring.

LIZ: Definitely boring.

Trey: And again, I was nine. I liked the stories that they gave in Sunday school, but when I tried to read my Bible [on my own], I got to one genealogy and was like, “Absolutely not.”

LIZ: I mean, trying to read your Bible as a nine-year-old is quite devout. I have an eight- and a ten-year-old and they are not picking up my Bible.

TREY: Yeah. What’s even funnier is, I went to school [for] broadcast journalism, did jobs in between, but ended up right back where I said I was going to be at age nine, preaching. My mom likes to hold that over my head.

Falling Into Ministry

LIZ: So then, how does Young Trey bored-with-the-Bible become Older Trey, a pastor with a seminary degree?

TREY: Church was my life up until 15 or 16, when the conversation shifted from “Hey, son, it’s time to go to church” to “Are you going to church?” I was like, “Wait, is this is a trick question? No, I guess I’m not going today.”

LIZ: ‘Cause you were a tired teenager.

TREY: Right. Then, for college, I was trying to go where the fun was at. I left Richmond [for the] University of Miami, and at the time, I wasn’t attending church because, I would say all the time, “Jesus is portable.” That was my motto. Like, “I don’t need to, I can do this on my own.”

But at some point, I met a woman who eventually became my wife. She didn’t grow up in the church, but she asked me to start going to churches with her. [So,] when we started getting serious, then we ended up at church.

And I started going to mid-week services, the pastor’s “question and answer” night… I would get there early and I would stay late and I would ask all these questions. I remember one time he was like, “Man, you be asking me all these hard questions, making me work.” I loved how transparent he was. I was like, “Yo, this is the guy. If there’s a church home for me, it’s here.” That’s probably the first time I can point to being serious about my faith. That was the first time that faith became personal for me.

As far as that transition into ministry though… it was kind of happenstance. At this church, the guy who was helping out with the youth ministry ended up moving, leaving town. I was like, these kids need somebody to help out. So, I started a youth ministry.

Liz: Wait, the youth pastor leaves and you’re like, “I guess I can do that.” And then you start something from scratch… as a college student. Is that what you’re telling me?

Trey: Yeah, that’s how that went. [Laughs]

Leaving a White Evangelical Seminary for a Historically Black Seminary

TREY: I did half my seminary in a conservative white Evangelical setting. Matter of fact, I was pretty close to graduating… but I [ended up] finishing in one of the nation’s six or seven historically black seminaries instead… which is very different.

LIZ: That’s a huge leap—from “I’m really close to graduating in this Seminary”…to “I don't want my degree from here… and I’d rather go elsewhere even if I have to start over because if I have to put this on my resume for the rest of my life it’s going to kill me inside every time.”

TREY: Oooh, are you in my head? That is literally the exact conversation [I had] with myself and then with my mentors, my pastor.

At the beginning, one of my first classes [at the white evangelical seminary], we had some prompt looking at the Genesis creation account. There was a question about whether [creation] was a literal six 24-hour days. I’d written, “Could it have been six literal 24-hour days? Yeah. Am I convinced that that was the case? Absolutely not.” My point was, I don’t think it’s any less miraculous if God creates the world over six billion years [‘cause] it doesn’t matter how much time you give me, I couldn’t do any such thing.

I grew up in the church, so [of course] I knew know there are a lot of people who read these things literally. [But] I remember the instructor replied to my answers by saying that I was “hedging” and [that I] “lacked conviction.” And in my mind, I was like, “Wait, if there was only one right answer to this prompt, then why would you ask the question?” That was the beginning [of seminary] and at first, I thought, “I can stick it out.” By my last year, though, I was saying, “I can; I just don’t want to stick it out.”

LIZ: That professor’s response was a dismissal: “You’re not allowed to think about that.”

TREY: I mean, they allowed it—just by asking the question—but [the sentiment was], if and when you think these thoughts, you are now out of bounds. We couldn’t even have a meaningful conversation.

LIZ: I’m struck that there’s no sense of empathy or curiosity about why you would think a different way, why you would have that question at all, where would that come from. There wasn’t a real engagement.

TREY: Exactly. [Before seminary], I literally [took] classes at the University of Miami where we would introduce ourselves [by] sharing our beliefs. I remember, I was in a class with 32 people and without fail, all of them said, “Oh, I was raised Jewish, I was raised Christian, but I don’t believe any of that anymore.” I was the only [student] who was like, “I’m a Christian. I was raised Christian and I’m still a Christian.”

I spent a whole bunch of time in an R1-Level research university. The school [had] an endowed chair for atheism and secular humanism. I [was] being exposed to all these ideas and I [had] kept my faith through the middle of all of this. [So,] when that professor said I “lacked conviction,” that rubbed me the wrong way. I felt like, “Who are you to tell me that I lack conviction when you have surrounded yourself with people who believe the same things as you?” I lack conviction? Nah, you don’t get to say that to me.

After that experience, I was like, “Okay, you guys aren’t serious.” And eventually, I told my mentor, “I’m not going back.” [I felt] there was way too much of myself that I had to check at the door. And I did not want this stamp [from them]. So, I dropped out. Actually, technically, I just stopped doing the work.

LIZ: Like your own form of protest.

TREY: When admissions said, “Hey, you’re on probation,” I said, “Don’t worry about it. I’m not enrolling here ever again.”

And then I transferred to the Samuel Dewitt Proctor School of Theology at Virginia Union University after I had been ordained in a nondenominational setting by a local church. My church is [a mix] of Pentecostal and Black Baptist; I’m “Bapticostal.” Now, I’ve been in ministry for almost a decade, and I’m currently the Executive Pastor at the Refuge Church in Homestead, Florida.

“My Only Conviction is Love”

LIZ: Seeing how you interact with people on Twitter, I see a lot of empathy in the way that you present your ideas—[you’re] quite gentle. Part of that might be that ecumenical bent that you have. But I wonder if it developed, too, through being one of a few Christians in your [university] setting. Did that have an impact on how you do ministry?

TREY: For sure. That gentleness that you’re speaking of in my twitter communications… it’s a humility that I try to embody. And I came by it the hard way.

When you’re surrounded by people who think the same way as you do, it’s easy to be loud and brash. Nobody’s really going to check you because you’re all on the same page. But when you have people [around you] who either don’t share your beliefs or find your beliefs laughable, it encourages you to reexamine [yourself] and to not hold [your beliefs] as tightly.

There’s always this voice in the back of my head that reminds me, You don’t know [for sure].

These are convictions—what I believe. That’s what faith is to me. But I don’t assume too many things to be absolutely true.

But the one truth I won’t compromise on is love—the idea that God is love, that Jesus is the perfect embodiment of love. Those are the strongly held convictions of mine. When I have [other] opinions, even if they’re well-founded, at the end of the day, no, it’s still an opinion.

What that [secular] environment did for me as a Christian…[was to] let me know that, yo, there’s a lot of people who are experiencing and processing things in a fundamentally different way than me. Because I counted them as friends and had real-life conversations, I could not call them stupid or foolish. They just landed at things differently than I [did].

Pastoring the Deconstructed & De-converted (and their Worried Friends)

TREY: I’m [currently] in this space where a lot of people are doing the whole “deconstruction” thing out loud. So there are people [around me] who will sometimes announce “deconversions.”

[When they do,] people [who are still believers] will reach out to me like, “Hey, will you speak to them?” I say, no, actually. I mean, I could, but I won’t.

[That’s because] I have spoken with enough of these people to realize that they don’t come by [their deconversion] lightly. And I don’t think highly enough of myself as a communicator to be the one who “wins them back.”

That’s not to say that I break off communication [with de-converted friends]—no, I’m still here when you want to talk. We can have conversations, even conversations about God and about theology. But I don’t talk for the sake of converting anyone.

I meet people with curiosity, and so they’ll meet me with curiosity. They’ll say, how do you do this? How can you reconcile this? How do you reckon with this? And I explain how I’m processing [my faith].

LIZ: I’m interested in the folks who ask you to be an intercessor to their de-converted friends or family. It seems like they want you to take on this relational responsibility that they have to this other person. What do you think is behind that instinct and how do you think people should be responding to others’ faith changes?

TREY: So, I think behind [someone reaching out to me] is the [instinct] that if we Christians are not winning souls to Christ, then we’re not doing enough.

LIZ: “Winning souls to Christ,” [meaning] making them say “the prayer”?

TREY: Yeah, that whole situation. We want to slap a jersey on everybody. And if somebody takes that jersey off, then no, this is hustling backwards. It feels like losing.

LIZ: Then we start throwing money at the situation: “We’ll pay you more! Just stay, please!”

TREY: The Bebbington Quadrilateral, the whole thing behind evangelicalism, shows that “conversionism” is one of the things we [evangelicals] identify ourselves by. We need more people joining up. So, if somebody’s leaving, not only is that bad for the numbers, that’s bad marketing. Because now people who are on the outside are going to ask this person why [they’ve left]. So, there’s this evangelical impulse [to do] damage control.

LIZ: I can exactly picture that in the case of, say, a former pastor who wants you to talk to his congregant on his behalf. Then the “bad marketing idea” seems like it could be motivating that pastor to ask for your help. But I’m curious about the more intimate situations, say, a family member or a close friend of a de-converted believer reaches out to you. What is the motivation behind their request? How is it different?

TREY: People genuinely think that if you leave the church, you’re on the path to hell. There’s concern… which I understand. I don’t cast judgment on the morals of anybody who would feel that fear [on someone else’s behalf]. But again, I don’t think I’m profound enough to be the one “to get [the deconverted person] back on that path.”

Plus, there’s another worry I have with this request. So, let’s say somebody announces they no longer believe the same things and they don’t hold the same creeds. But they’re still living the same way [as when they believed]. Is it the belief alone that… get[s] us into heaven? I could see if they announced that they were no longer Christians and then they went on this giant murdering rampage, in which case, don’t call me. I’m not the guy for that job.

LIZ: That’s actually the police and a therapist (or ten).

TREY: Right. But the emphasis is on “beliefs,” not actions.

So I try to challenge [the one reaching out] by saying, “Okay, how are they [the deconverted/deconstructing] living? Would you call their behavior and the relationships that they hold… are they loving? Are people drawn closer toward wholeness and liberation in interacting with this person?”

At the end of the day, I am not too concerned with anyone’s “confession,” what your [stated] belief is. I’m way more concerned with how you’re living. And that [goes] for anybody of any religious identification. I’d much rather hang out with a loving and friendly atheist than a loud, obnoxious, insufferable Christian.

Of course, in the moment, it doesn’t bring peace to many people to hear that from me. But look, we need to understand that this person’s journey is their own. They’re going to have to live with that. So, can you find a way to maintain community even without this credal bond? And if you cannot, how authentic was the community you shared in the first place?

Creed vs. Practice

LIZ: I like that distinction between how a person describes their beliefs versus how are they acting. Of course, part of the issue we’re seeing in the evangelical church recently is that we have these stated beliefs, but our lived expression does not match what we say we believe. And I’m curious what role stated beliefs and creeds should actually play in American Christianity.

Personally, I’ve struggled to figure out my own place in the church because I actually believe it's reasonable for an organization and institution to have boundary lines, to say “This is what defines us, this is our identity as a people group, as a tribe.” But that can be exclusionary, too, in a way that harms outsiders and actually undermines the integrity of our identifiers.

So, when do those self-identifications and creedal alliances become too strongly held? Why do you think evangelicals, in particular, place such a high emphasis on belief so that we lose sight of the importance of the lived expression of our faith?

TREY: Creeds definitely have a role in the church. They do help provide boundaries. The right of self-definition is an essential aspect of what liberation requires: the right to define yourself and your community.

That becomes problematic when the boundaries that you rightfully put in place are then used as a means of condemning those outsiders, when you [start to] call anyone outside of your community an enemy—not only your enemy, but God’s enemy. That’s presumptuous and wrong.

At no point in history has there been anything like a unified Christianity. We don’t see it in the Bible; we don’t see it throughout history. There’s never been just one way of looking at this [God]. So, to take these boundaries and assume, “This is the only way and everybody else is wrong,” that’s hubris. That’s the opposite of the life and the way of Christ. And that’s not to say that we don’t have boundaries anymore, but you have to accept the limitations of your community.

The moment you start casting people who are outside of your community into a hell that you don’t have authority over, now you’re getting a little too big for your britches. Jesus said himself, “Other sheep I have who are not of this fold.” So, we have to recognize the validity of other people’s experiences and the truth claims of other communities even as we endeavor to define ourselves.

Making Peace with Diversity and Disagreement

LIZ: You’re making a distinction between making someone else into an enemy versus recognizing that we are each distinctive individuals and communities. You’re saying, differences are not, in and of themselves, wrong. I know evangelicals who would say there is no distinction between someone who’s different and an enemy; those are the same.

Of course, there have been movements toward diversity and greater acceptance of differences within the American evangelical expression—at least, theoretically. Usually this comes up about race and ethnicity, though nothing seems to stick.

TREY: A lot of this stuff happens in the theoretical.

LIZ: A lot of it stays theoretical.

TREY: And that’s a problem for me. One time on Twitter, someone said to me, “I have more in common with a Christian in China than I do with an atheist across the street.” And I’m like, “Bro, what the hell are you talking about? How would you know? You can’t have a conversation with the Christian in China ‘cause you don’t even speak the same language.”

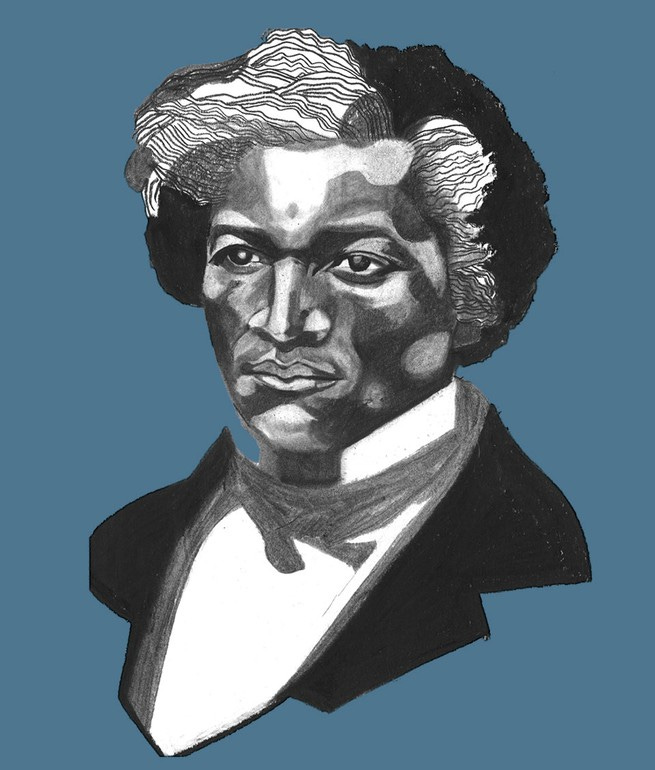

I can tell you right now, there’s a bunch of Christians right now in the United States that I don’t have anything in common with. Frederick Douglass said, “Between the Christianity of Christ and the Christianity of this land, I recognize the widest possible difference.” That’s still true, to the point where it’s almost a mockery.

So, I understand his point. In theory, that Twitter post sounded good. “Oh yes, we’re all brothers in Christ.” Even if one brother lives in China and one lives in America. But does that make any sense?

LIZ: No, it doesn’t make any sense at all. Because the fact of the cultural difference is significant. That statement—“I have more in common with a Christian in China than I do with an atheist across the street”—assumes that the gospel lives in this transcendent realm that is entirely untouched by culture. And Liberation theology pushes back hard against that idea. Because our culture, our bodies, all of that is a part of this gospel story. There’s no future for theology if it’s not a theology that happens now, that’s enacted. Without a theology that means something in our everyday lives and interactions, then what’s the point?

TREY: People sometimes say, “Stick to the gospel.” Well, okay, what do you mean by that? Dr. Theron Williams tells a story in his book Black Church/White Theology where he’s asked about “the gospel” and the questioner points to Paul. And Dr. Williams says, “That is indeed what Paul said. What did Jesus say the gospel was?”

Jesus said, “The Lord’s favor is upon me and I’ve come to proclaim freedom to the captives, restore sight to the blind,” all these things. (Luke 4:18-19) Jesus in the Gospels says this good news ought to be changing the lives of people in very tough situations.

“Outsider Theologians” Offer a Corrective for White Evangelicalism’s Eurocentric Theology

LIZ: I’ve been doing a lot of “outside” theological reading [for my own book project]—I say “outside” in the sense of “Outsider Art.” Not that they’re lesser in any way. But these theologians are not taught the same in theological spaces as European theologians are. For example, James Cone, Howard Thurman, Delores Williams… In theology courses in my white evangelical college, I never read them. And some of that is my own ignorance, right, not only the institution failing me. But these theologians are of special interest to you.

TREY: What “Outsider” theologies—like liberation theology—do is give you permission to ask questions like, how does that social location impact the way that Paul approaches the Hebrew texts? As opposed to the more reformed view where [they] try to remove the humanity from the Sacred Texts. But liberation theology acknowledges, this is not only “the word of God,” it’s also a Divine-human interaction [that made the Bible].

So, I try to cast a wide [theological] net. For the most part, because theological education tends to skew so heavily one way [toward white, European and male voices], I try to be intentional about plucking voices from what we would consider the “margins” and centering those voices.

LIZ: Who are the theologians that have really inspired a different way of thinking for you?

TREY: I definitely have an admiration of Dr. James Cone… Particularly towards the end of his career when he was open about some of the blind spots he had towards black women and things of that nature. Delores Williams, too. Seminaries do a disservice if she’s not included in the curriculum. Even if you’re not co-signing it, a systematic theology course should at least let you know that there are people out there doing this kind of work.

LIZ: [As in,] yes, there is a thing such as womanist theology, [centering a black female reading of the Bible,] and it should be discussed as a legitimate theology and not ignored. In a lot of these classes, it might come up as a secondary item of study, but it won’t in the main theological coursework, in the main syllabus.

TREY: Exactly. I’ve learned a lot Dr. Wilda Gafney, I’ve learned a lot from Dr. Mitzi J. Smith, Dr. Yolanda Pierce…Dr. Drew Hart is …somebody that I look up to. Who Will Be a Witness? is one of the dopest books out there. I lean on those people a lot, in particular as a black man, because they have found a way to stay true to ourselves as black people while still maintaining academic integrity.

[Also] Pete Enns [has] been able to bring a level of expertise and present it in “popular,” everyday language. I mean, “The Bible for Normal People.” Richard Elliot Freedman—he’s a Jewish scholar. And Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg is amazing.

Reexamining the Tradition of the Nuclear Family

LIZ: I wonder, which Eurocentric “orthodoxies” have you personally had to either discard or sort of re-member to figure out what is good and what is not? And what do you wish that the white church would throw out?

TREY: The construct that I spent the most time examining—not throwing it out—is the traditional ethics around marriage and sexuality. Because one of the things you won’t find in the Bible is a society in which marriage is built around romantic interest between one man and one woman. [Marriage] is fundamentally about establishing contractual relationships to preserve estate within kinship networks. The only time I can expressly find a command toward monogamy in the Bible is in the requirements for an elder—where it says, “the husband of one wife…” And the construct of the nuclear family is not really grounded in the Bible at all. But it’s very much espoused by Western Christians as “tradition.”

The tradition of the “nuclear family” has confronted me with the depth to which Western culture and Christian teaching have become wedded. Examining marriage within the Bible has forced me to confront the ways that we have sanctified and baptized western culture as the default. Once we loosen our grip on the idea that Western culture is [necessarily] Biblical, then we can stop pathologizing people and begin this process of re-humanization. We can actually start addressing the needs [of people outside the norms].

Now, that’s not me saying, “Oh, we need to throw monogamy to the wind…” I’m married to my wife, I love my wife, I got my three children. We got the average American family over here.

But 9 times out of 10, if you walk into a conservative setting—theologically and politically conservative—and you start bringing up how to help marginalized communities, they’ll say, “We need more fathers in the home.”

Okay, that solution makes sense based with the structure of the pater familia, right? That makes sense in this Western nuclear family construct. But at what point does Jesus ever walk into a situation and say, “The solution… is a man back in the home”? That doesn’t happen. We don’t see that in the Bible.

And Jesus wasn’t born into a nuclear family. Normally when I say that, people go up in arms. Like, “No, the nuclear family is all over the Bible.” I’m like, “I promise you it’s not, not one single time. It just isn’t.” That’s not me condemning the nuclear family, that’s me saying it’s not a Biblically-grounded concept.

We live in a culture that contains more variety than the “Western nuclear family construct.” So then, what does Jesus require of us now?

Contextualizing the Bible for Today

LIZ: Essentially, you’re saying we should actually read the scriptures, understand its context, compare it to our own context, see where the overlaps are, and then seek the spirit, seek wisdom to apply it today. Like, we need to translate what we’re reading.

One of the frustrations I have felt within evangelicalism is that the way we are addressing theological issues today is to use theology that was written 50, 80, 100 years ago. [But] those people had never seen a computer, they don’t know what the internet is. Obviously, those older theologians have things to say and there’s truth in their writings. But we need a whole new crop of writers and theologians and pastors to examine what’s actually happening right now. That’s how we create the theology the future. There are ways in which theology is timeless, and there are ways in which it continues to progress. Sometimes, there is no easy cut and paste between the two.

TREY: Right. I think the moment we recognize the wide gulf between the culture of the Bible and the cultures of our own traditions—that they are not the same—then I think we’ll become better at embodying the love and the call of Jesus where we are right now. And it requires both courage and integrity.

Like, people ask me, how do I arrive at a place of affirming women in ministry? Oh, this is an easy one for me. ‘Cause many of the same passages that clearly indicate that Paul had men in mind for this [pastoral] role also suggest that Paul never clearly condemned slavery. And we, for the most part, recognize now that slavery is not good, it’s not ideal. The Bible doesn’t come out and say that, aside from God coming and freeing the Hebrews from slavery situation [in Exodus].

LIZ: Which is a very clear sign that slavery is wrong.

TREY: Right, but the same God also gives rules for how to treat enslaved people after that. So, I’m willing to grant that there’s some ambiguity there. What is more important to me is that, as a society right now, we have decided, we’re not okay with slavery ever. That’s important [to our historical] context. We don’t live in the time the Bible was written, we live in this society today.

So, what do I do with a Scripture like, “Slaves, obey your masters”? (Ephesians 6:5). I say that Paul lived in a different world. That Paul struggled to imagine a world in which slavery was not the norm and so Paul clarified how to own slaves in a time when slavery was the norm. If I read with that context in place, what do I do with this Scripture?

If I were to take a [literal] stance toward “Slaves, obey your masters” as a black man who is the descendant of enslaved peoples in America, that would be hypocrisy.

And I would be lacking in integrity as a pastor if I applied a [liberation] reading about slavery to myself but then applied a literal reading to women, saying, “No, but we absolutely need to keep women out of ministry. That still applies.”

I point out to people the holes in their literalism sometimes by asking, “Okay, what do you do with the fact that Paul says [an elder should be the] ‘husband of one wife’? Are single men allowed to be pastors?”

They’re like, “Well, yes, because that’s describing faithfulness.”

And I’m like, right now, you’re already making interpretative choices. If that’s the case, why are you so sure [Paul] meant faithfulness here, but he definitely meant gender or sex in another passage?

For me, it comes down to courage. We need to say, I believe this is what Paul meant and I’m not as concerned about the literal instruction in my context. And then we need the integrity to say, look, if this is the way I’m reading this for me and my people, then I need to extend a [consistent interpretation] to these [other] people, you know?

The Ties Between Biblical “Inerrancy” and White Supremacy

TREY: Many Christians are like, “Oh, the Bible doesn’t have any contradictions.” Who said that? Because you don’t have to get past Genesis 2 before you find a contradiction. What’s the order [of creation]? Was it man, woman, animal? What’s happening here? But [contradiction] doesn’t make the Bible any less true. Stories are very powerful. Stories orient societies. But some people insist that viewing these Bible stories literally is the only way to faithfully love God. (Which is also not a stance you will find in the Bible.)

LIZ: Well, frankly, that’s a lie they’ve been taught. I think at some point some preachers who were influential decided that it was much simpler to flatten these stories for the sake of general understanding.

TREY: I have this theory [that], particularly in our American context, that this push toward fundamentalism and literal understandings [of the Bible] throughout the nineteenth century and the turn of the twentieth century was tied to a vested interest in reading the text as racist.

So, I am naturally suspicious of the Chicago Statement on [Biblical] Inerrancy. Get that thing away from me. I know who the architects of this thing were—people who would be happy to see me in chains still. I do not necessarily mean the signatories of the statement, but the thinking and the hermeneutics that led to such a statement at all. There’s not always an innocent or even neutral intent driving inerrancy. Sometimes there’s a nefarious motivation, like justifying racism, sexism, or some other hierarchy. And that’s why you [wanted to] read the text this way.

[I wish I could say,] I need you guys to wake up because this [move toward inerrancy] was a response to something.

LIZ: Specifically, a response to the Civil Rights movement, a growing movement of egalitarianism in the church, etc., etc.

TREY: Right. And “inerrancy” is honestly such a strange way to read any book.

LIZ: It’s not completely unheard of before evangelicalism—within the midrash, for example, there are lots of stories that play with the idea of “inerrancy.” But, of course, the Jewish midrash itself is an ongoing conversation with many theories and stories and different interpretations of the Scriptures. Whereas we American Christians approach our Scriptures as if there’s only ever been one way to read the Bible and it’s the most obvious way. “Whatever is the simplest, the plainest from my Western suburban perspective, that’s the way to interpret it.” We ignore the fact that people have been fighting about these Scriptures for thousands of years.

TREY: Since forever.

LIZ: Thousands and thousands of years. So maybe it’s going to take us a little more time than a cursory glance to understand what any passage in our ancient sacred book means.

“Put me where you want me”: Being An Ally

LIZ: Last question for you: Obviously, I am a white liberal woman. As someone who is seeking to be an ally, I have often found myself in a tough middle space where I want to talk about these issues, but I know I’m going to say stupid things occasionally and be wrong. I’m okay with being wrong, I’m okay with being corrected, but I want to ally with BIPOC folks tenderly. So, I often wonder, what is the appropriate role for white folks in activism for and with BIPOC folks?

TREY: It is a matter of learning to follow. I’ll give a concrete example. Let’s say you want to get your hands dirty and make some effective change. You got to identify who’s already working toward that change. ‘Cause the moment you think you about to build it from scratch is the moment you going to be doing too much. You’re going to step on somebody’s toes or have to deal with the critiques of “white feminism ignoring black women” and “white women actually holding up the patriarchy…” Which are legitimate critiques.

But if you’re serious about the work, find black people who are already doing the work and ask them straight up, “What you need me to do?” And then do that thing. And if there’s ever a time when they want you to take on more responsibility or leadership, they’ll let you know. But a lot of times, the problem is, [white] people end up taking on accolades and roles and postures… [and BIPOC activists] are like, we don’t need you to do all that.

It’s always interesting that I ended up in this level of ministry because I don’t feel the need to lead all the time. There are lots of situations where I’ll show up asking, what do you need me to do? What do I do with my hands?

LIZ: The attitude is, “Put me where you want me.”

TREY: Yeah, that’s the posture that’s gonna get things done. Because at the end of the day, we have to wrestle with a lot of legitimate, justified trust issues. It takes intentional listening and being willing to get uncomfortable. Nothing changes if we don’t go in with a mindset of, okay, this is going to be uncomfortable.

And I need to get comfortable being uncomfortable.

About Trey Ferguson

Trey Ferguson is a minister, writer, and speaker, with an MDiv from the Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology at Virginia Union University. His thoughts on faith in an evolving world can be found on the Three Black Men: Theology, Culture, and the World Around Us and New Living Treyslation podcasts, in

newsletter, and at @pastortrey05 on twitter and instagram. He lives in South Florida with his wife and three children. Learn more at pastortrey05.com.(P.S. He also has a book coming out soooon! TBA)

ICYMI, I’ve interviewed other like-minded progressive Christians, such as:

Tim Whitaker of the New Evangelicals,

Sara Billups, author of Orphaned Believers,

and J.S. Park, author, hospital chaplain, and father to an adorable toddler ;-).